Collection Features

Notable Work from Our Collections

FWMoA Highlights

With nearly 5,000 American paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints and photographs, our collection is a diverse reflection of American history. The FWMoA collection includes art created after 1850 from notable artists like Janet Fish, George Inness, Alma Thomas, Mark di Suvero, Richard Greenough, Chuck Close, Jasper Johns and many more.

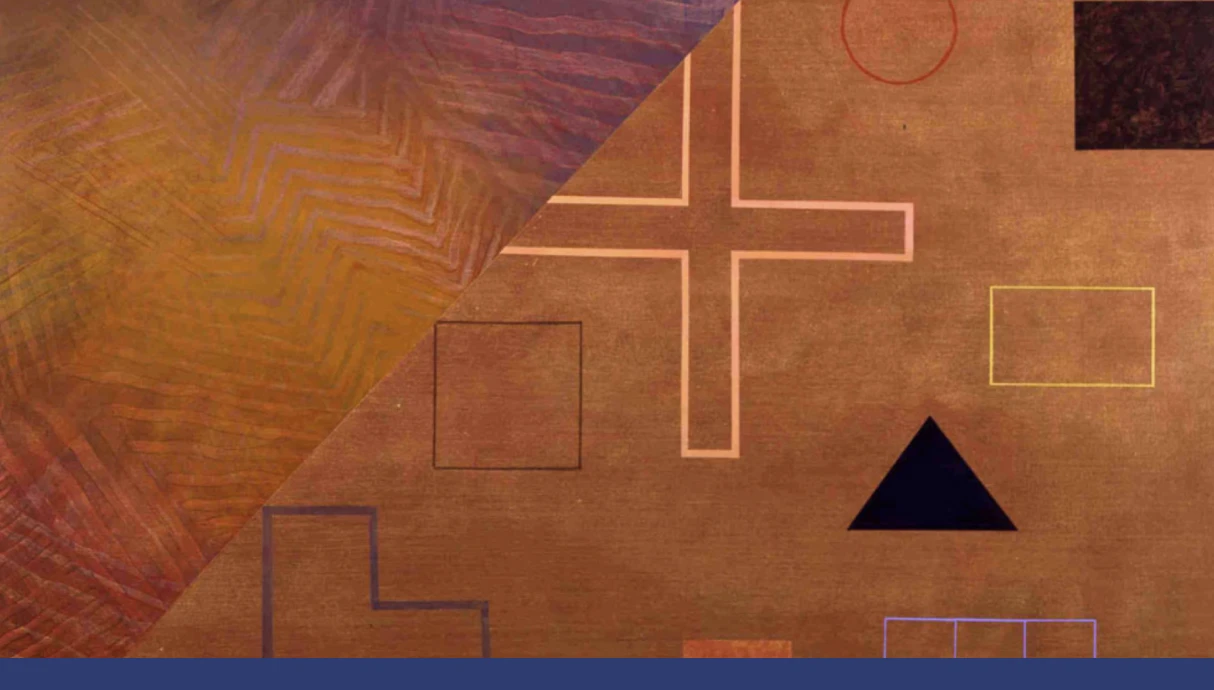

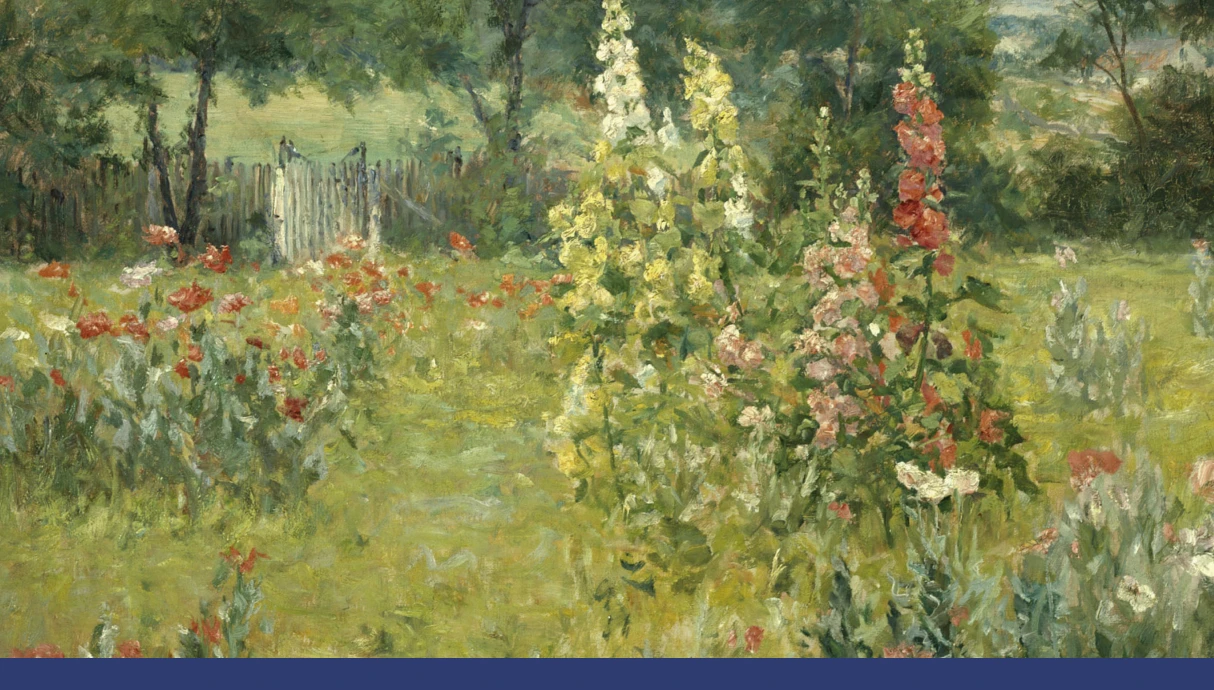

Indiana Impressionism

Impressionism represents an important turning point in American art. It strayed from what was taught in academic art and is rooted in techniques that evoke emotional and sensual responses (as opposed to detailed work that might represent realistic elements of people, places or things). Our collection of Indiana Impressionism started with a generous gift of ten paintings in 1921 from Theodore Thieme. These paintings featured the work of notable Brown County artists William Forsyth, J. Ottis Adams and Homer Davisson.

Indiana Impressionists are known for their love of the untouched natural environment, isolated from developed towns and cities, and their compositions emphasize the trees, hills and natural lakes of Indiana’s landscape. Their works were begun (and often finished) outdoors, with a range of colors dotting the canvases to represent changing light and shifting winds. The colors in these works are warm and rich, with hues of red, orange, green and brown used to convey the colors of Indiana.

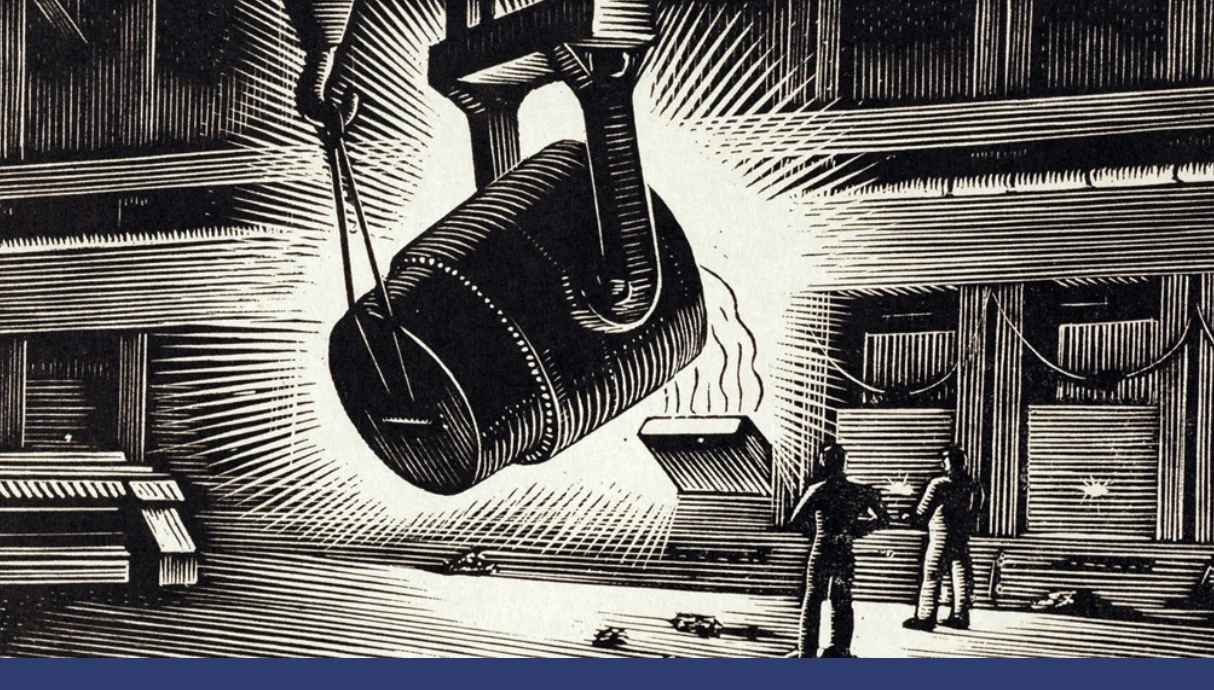

Prints and Drawings

The history of American printmaking stretches over the last three centuries and is as vibrant as any other medium in the visual arts. But, many people are unfamiliar with the process of printmaking; it’s a delicate and complex medium. To demystify it and open everyone’s eyes to the rich and engaging realm of prints and printmaking, the Fort Wayne Museum of Art has created a center through which the public can explore the many dimensions of prints, their makers and their processes. Much of this collection is housed in the Print and Drawing Study Center, a hybrid gallery and research center open to the public.

Sculpture at FWMoA

Enjoy a half hour walking tour of the sculptures found in and around the grounds of the Fort Wayne Museum of Art and the Arts United Center. Starting in the Sculpture Court with Cary Shafer’s Tilted Arch, move through the museum and out to the front patio to see David Black’s Crossings and Mark di Suvero’s Helmholtz in Freimann Square.

These images are selections from our collection and may or may not be on physical display, although some are shown from time to time. Please visit the exhibitions page to see what’s on display in our galleries.